If our system is resilient enough to respond to the fascist regime through designed self-correction rather than revolution or civil war, the main mechanism will be the 2026 midterm elections. Even normal administrations have historically done quite poorly in midterms, with exceptions like 1998 and 2002 being outliers. But the Biden administration didn’t do all that badly in the 2022 midterms, and that’s actually not encouraging.

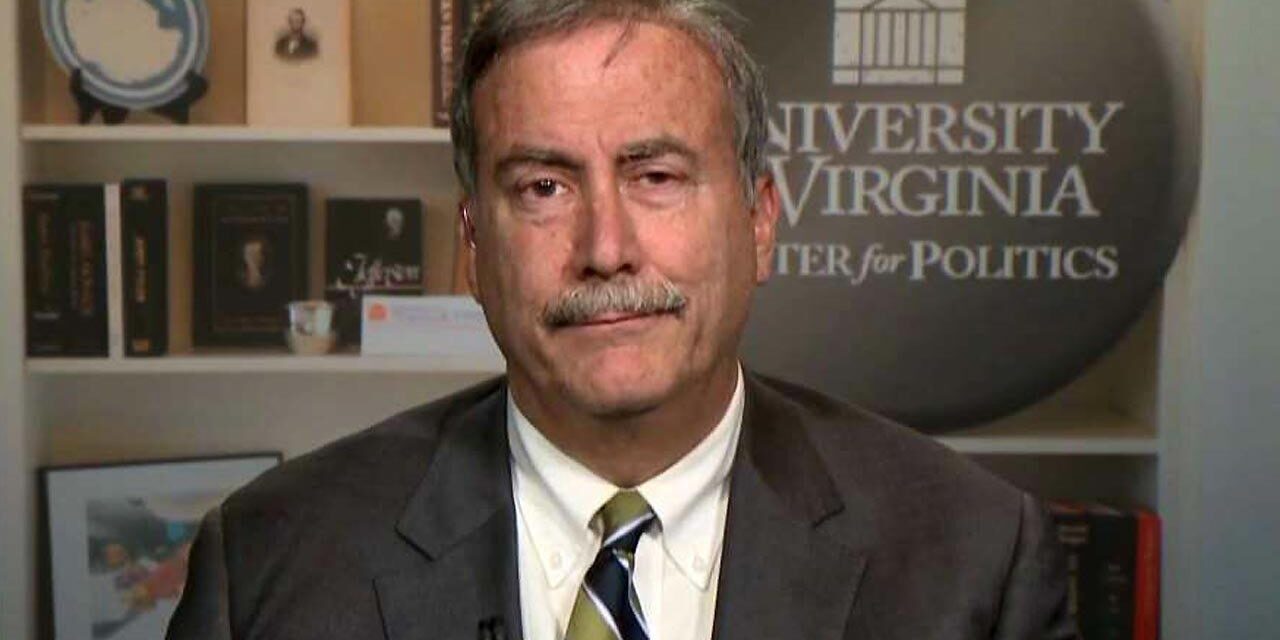

As Larry Sabato explains, the odds of a big wave in the U.S. House of Representatives are not great, even if a change in control of the lower chamber is very achievable. The recipe for a big wave election in which dozens of seats are gained by the minority party is cooked up in the previous presidential election. The way it normally works is that the party of the winner of the presidential election will win many marginal seats. These seats will not be safe for the new incumbents in the next election cycle.

There are two main kinds of congressional districts that fit into this category. In a scenario where a Democrat wins the presidency, there will be Republican members of Congress who lose because their district leans Democratic in the first place and their hold on the seat was always tenuous. Then there will be seats that are only modestly right-leaning, and flip over to the Democrats when they have a good election cycle. But the competitiveness of the seats is precisely what makes them likely to flip at the first opportunity. The more of these seats there are, the larger the potential for the exchange of many seats in a midterm election.

What’s happened in recent years, however, is that there are very few Republicans serving in left-leaning seats or Democrats serving in right-leaning seats. Basically, the House of Representatives is ideologically sorted pretty well, and this is the primary reason that the Republicans did not see the promised “Red Wave” in the 2022 midterms. Yes, they won three Senate seats and enough races in the House to seize a very narrow majority, but it wasn’t a good performance in historical terms for a minority party in the first midterm after a new president is elected, especially an unpopular one.

Looking ahead to the 2026 midterms, the Democrats face the same limitations for the same reasons. Ironically, the fact that the GOP didn’t win as many seats as they hoped in 2022 or 2024, means that the Democrats are unlikely to win as many as they hope to in 2026.

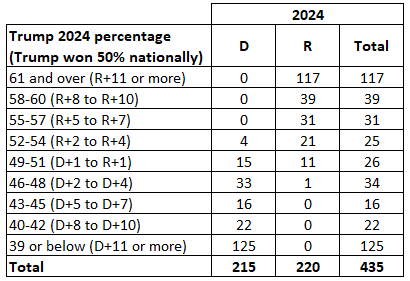

Here you can this in visual form, with a focus on the 2024 elections.

The current makeup of the House is 220 Republicans, 212 Democrats and 3 vacancies. The three vacancies are due to Democrats Raúl Grijalva, Sylvester Turner and Gerry Connolly dying in office since the November elections, and all three of these vacancies are likely to be filled by Democrats after scheduled special elections. So, most likely, the Democrats will only have to net a gain of three seats to win a 218-217 majority. It won’t take much of a swing in the D+1 to R+1 districts to make that happen. But there’s just not a lot of low-hanging fruit, with only one Republican serving in a district that voted D+2 for Harris or better. There’s actually more low-hanging fruit for the Republicans.

To have a good wave-type election, the Dems are going to have to dig into the 21 R+2 to R+4 seats, or even some of the 31 R+5 to R+7 seats while also protecting their own vulnerable members.

When it comes to acting as a check on the fascist regime, even a one-seat majority in the House would be hugely beneficial because it would provide the Democrats the ability to hold hearings, stop any unwanted legislation from passing and to have a seat at the table on all government funding decisions. But keeping such a small majority in line could prove difficult considering that the new members will all be serving in highly vulnerable seats. A bigger majority would be more secure and easier to defend in 2028, and it would also send an important message to the courts, the media and the rest of the world. We want fascism to be perceived as weak and a failure, and as something that can be successfully fought. We don’t want people and institutions failing in line out of fear and hopelessness.

My hope is that some of the headway we need to make in these R+2 to R+4 districts will be gifted to us by unpopular decisions the regime makes. But we also need candidates who are natural fits for these constituencies.

On Tuesday, the Washington Post reported on the internal debate that is raging among Democrats about the cost of buzzwords like “intersectionality,” “Latinx,” and “equity.” One side sees this “woke” language as alienating and costly, while the other side says these concerns are overblown and that they aren’t costing the Democrats winnable elections.

Personally, I only care about jargon when candidates use it. I don’t care what people say on campus or among activists and organizers. When it comes to candidates, they should talk plainly and in terms that are recognizable and readily understood by their constituents. This is one reason why I don’t think candidates should rely very heavily, if at all, on talking points ginned up in Washington DC by party elites. They can use polling data provided from DC to understand how issues resonate and some of the language that tests well, but they need to rely more on their direct experience and intuition from living in their communities to develop their messaging plan.

They will hopefully know pretty precisely why the Democratic Party has not been doing well where they live. What they don’t know at the outset, they can learn on the campaign trail while interacting with potential voters. In the upcoming midterms, it will probably be most important to understand precisely what constituents are angry about with respect to the regime and its congressional enablers. This is not going to be positive messaging election, although that doesn’t mean a candidate cannot express some optimism here and there.

The party as a whole can help or hinder candidates running in right-leaning districts, but they should be clear that the relative success of the campaign will hinge on how many of these districts are won. My suspicion is that there really ins’t a unified national Democratic message that will be more of a help than a hindrance. Some constituencies will be angry about tariffs and prices, others about local job losses, others about agricultural issues and damage to the clean energy industry. Still others will be focused on cuts to entitlements and Medicaid. Most, but not all, of these issues will have a particular local flavor that isn’t really conducive to a national message.

It’s not a terrible idea to have some pissed off former Republican candidates who retain a few conservative political stances, but I wouldn’t make that the primary recruitment strategy because I’d rather see an authentically left-leaning populism take hold and make a pitch for these voters’ support. I can’t think of a better cycle to try this out, because Trumpism has really revealed itself in the second term, and there’s plenty of opportunity for folks to have second thoughts about what right-wing populism really has to offer compared to what it promised.

I believe Sabato’s pessimistic analysis is flawless, but I’m not unhopeful that the Dems can have a great wave election if they don’t get in their own way.

Adding: I don’t think Democrats will need much of a positive agenda to campaign on. I remember a couple of successful “negative” referendum campaigns that won by large margins after trailing in the early polling.

One had for a slogan: “Question #2, Bad for You/Vote No on #2” and it was plastered everywhere: bumper stickers, billboards, lawn signs. (This was a pre-internet campaign run by the state Building Trades Council. Post-election polling showed that most people who voted “no” didn’t know anything about the question other than it was “bad”.

The slogan for the other (different election cycle) was “Vote No on #3/It Doesn’t Make Sense”. It wasn’t a high-profile issue, and the ballot language was complicated…so most voters got to the polls and agreed: “This doesn’t make any sense. I’m voting ‘no’.”