When I wrote “What Trotsky Can Teach Us About Trump” almost a month ago, I detailed a fundamental split between Leon Trotsky and Josef Stalin. In that case, the dispute was over whether communism could succeed in Russia without it also succeeding in the more advanced economies of Europe and the United States. Stalin said it could and Trotsky said it couldn’t. Stalin won the argument by force, but one could argue that Trotsky was proven right in the end.

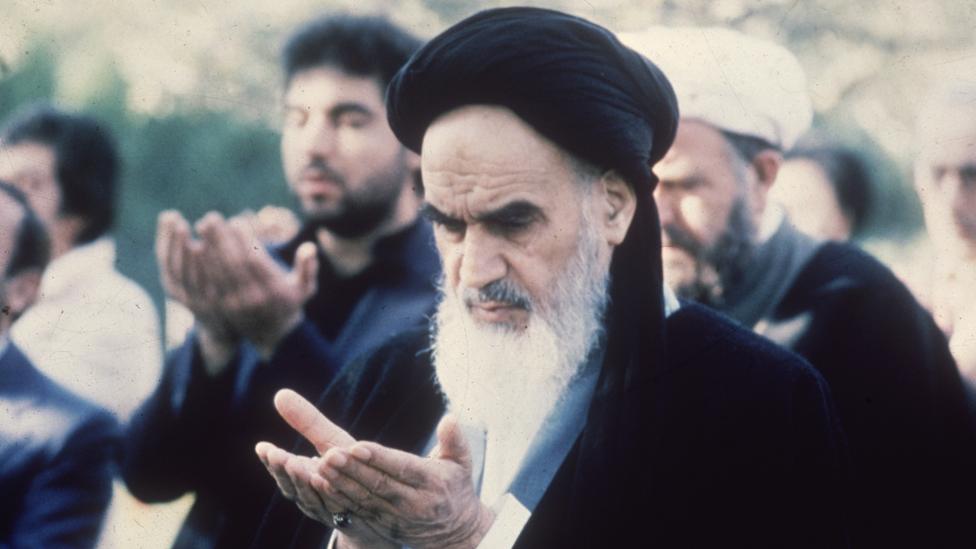

Iran had a similar disagreement, but in reverse. The spiritual leader of the Iranian Revolution, Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, believed that the revolution should be spread far and wide in the Islamic world. His chosen deputy and successor, Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri, believed that Iran should not invest in exporting the revolution. For this reason among others, in March 1989, Montazeri was removed from his post, and he was stripped of his “Grand” title.

This wasn’t the only disagreement Montazeri had with Khomeini. It should be remembered that the uprising against the Shah in the late 1970s was broad and spanned the entire ideological spectrum. Khomeini called for an Islamic government by didn’t define what that meant. He repeatedly denied that his ambition was to have clerics rule. There was no consensus on what should replace the Shah’s government, but strong agreement that the Shah was not respecting Iran’s constitution or people’s freedoms and rights.

What happened instead is that Khomeini initiated something called “Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist,” or “Velâyat-e Faqih” in Persian. The idea behind it is rooted in Twelver Shi’a Islam. In about 873 CE, the Twelfth Imam (successor to Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali), who was a child, mysteriously disappeared. It is believed that he entered into a state of “occultation.” Basically, he is hidden from mankind but will eventually emerge much like Jesus of Nazareth, to establish peace and justice at the end of time.

Meanwhile, however, there is a question of who has the right to rule over Muslims. Khomeini argued that “only those who have knowledge of Sharia should hold government posts, and the country’s ruler should be the faqih (a guardian jurist, Vali-ye faqih), of the top rank—known as a Marjaʿ—who “surpasses all others in knowledge” of Islamic law and justice.”

In this, Khomeini was a theological innovator, and the vast majority of Grand Ayatollahs disagreed with him. This probably remains true even to this day. Montazeri, however, agreed at least in principle, which is why he was chosen as second-in-command and successor. But Montazeri saw the role of the guardian as more advisory than executive. He supported a democratic system of government overseen by a guardian who would ensure it abided by Islamic principles.

He came into conflict with Khomeini in the mid-to-late 1980’s over a variety of issues. One was permitting the existence of political parties, which technically happened in 1987. Another was the aforementioned exportation of the revolution through proxies such as Hezbollah. And, finally, Montazeri strongly objected to the treatment and execution of political prisoners.

By this time Khomeini was ill and knew his time was limited. Finding a successor other than Montazeri was problematic primarily because he couldn’t find a suitable expert Ayatollah who followed his principles for Islamic governance. So, on his deathbed, he called for a constitutional convention and amendments were made to Article 5 of the constitution. Originally, Article 5 said that the guardian had to be a marja–essentially a Grand Ayatollah. Once this change was made, it paved the way for Ali Khamenei to serve as his replacement. Khamenei was not a Grand Ayatollah and was not known for his religious scholarship.

Khamenei assumed the role of guardian on August 6, 1989 and has remained Iran’s supreme leader ever since. Montazeri remained a critic and spent 1997-2003 under house arrest. He was prominent in the uprising against the fraudulent 2009 Iranian elections that came close to toppling Khamenei’s government. He passed away in December of that year.

Khamenei has been true to Khomeini’s vision. There has been a patina of democracy in Iran, but all executive responsibility remains with the guardian who determines who can and cannot stand for office. The revolution has been exported as much as possible, especially to Syria and Lebanon, and later to Iraq. The people of Iran are subject to fundamentalist interpretations of Twelver Shi’a Islam, with the most visible expression of this the compulsory wearing of a hijab for women.

Needless to say, the Iranian Revolution to replace the Shah’s monarchy did not have to turn out this way. It could have developed more in line with the vision of Montazeri. It could have developed without the heavy hand of any Ayatollah at all.

Today, Khamenei is 86 years-old and widely despised. He is correctly derided as a dictator. His determined and decades-long efforts to export the revolution have failed in spectacular fashion. His ally in Syria, Bashir al-Assad, is in exile in Russia. Hezbollah has been routed in Lebanon. Even his efforts to prop up the Sunni-led Hamas in Gaza is in literal ruins.

There’s little reason to believe he has a firm grip on power, and even less to believe there is a successor who can hold things together. And this was true before Israel began attacking the county and assassinating top generals and leaders.

Having said that, he has had three decades to seed Iranian society with loyalists and people whose personal status and prosperity are dependent on the continuation of his system. The same was true in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and we saw how that led to a furious insurrection once he was deposed.

Still, Iran, even under the tyrannical rule of a guardian, is much healthier and naturally cohesive than Iraq ever was. It’s true that it also has aggrieved ethnic and religious minorities, but they come nowhere near forming a majority, as they did in Iraq. Iran has a very imperfect democracy, but it still has established norms for conducting elections and experienced officeholders.

I don’t believe than Iran will necessarily fall to pieces the way Iraq did if the government falls. It has the potential to operate the way it should have from the beginning, in a true democratic way.

But it has always been the case that the best way to test this theory is for the Iranians to rise up without outside help or compulsion. A revolution imposed from Israel is the absolute worst beginning point I can think of, and United States involvement is a close second. The problem is quite obviously that whoever is acceptable to Israel and the United States will immediately lack legitimacy with the Iranian people.

I’ll go even further than this and state that the present leaders of Israel and the United States are the worst people in either country’s history to try to confer any legitimacy on a replacement government in Iran.

If the Iranian government falls, very few people will lament its fate. At this point, even the government in Germany seems to be eagerly awaiting that outcome. But it’s a tricky business. I believe the focus should be on what is best for the Iranian people, and that means their country should not be reduced to rubble and they shouldn’t suffer under hated foreign occupation.

Maybe the best outcome now for the Iranians is that elements of the military defect and toss the clerics out, and then quickly move to hold free and fair elections. I can definitely see that happening considering the pressure military leaders are under at the moment.

Would that satisfy those who are determined to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon? I really don’t know because I think the people of Iran believe they have a right to enrich uranium and have a nuclear energy program, and that would be reflected in a truly democratic government. I also think that the experience and humiliation of these Israeli attacks will convince the Iranian people that having a nuclear weapon is a needed deterrent to ensure their national sovereignty going forward. Perhaps they can be convinced for practical reasons not to pursue one. I think it will take a long time before the international community, and especially the U.S. and Israel, can be comfortable allowing a nuclear program to proceed unmolested.

As for what will happen in the immediate future, I don’t think things will deescalate so long as the Iranian regime remains intact. Their revolution has reached an end point, much like the USSR of Stalin and Trotsky reached an end point. But, remember, the fall of the USSR was messy and involved securing nuclear materials. And it has remained messy, as the war in Ukraine makes painfully clear.

I am not without hope that the Iranians are on the cusp of a brighter future more in line with what should have happened back in 1979, but it’s hard to be optimistic with people like Trump and Netanyahu on the other side.

It is, I think, a mark of how removed from pragmatic reality Netanyahu and Trump are that they have their countries on the brink of all-out war with a middle-income nation of 90 million people (Israel has 9 million) 1,000 miles and 3 borders (Syria, Jordan, Iraq) from Tel Aviv. ( Not to mention 6,000 miles from DC.)